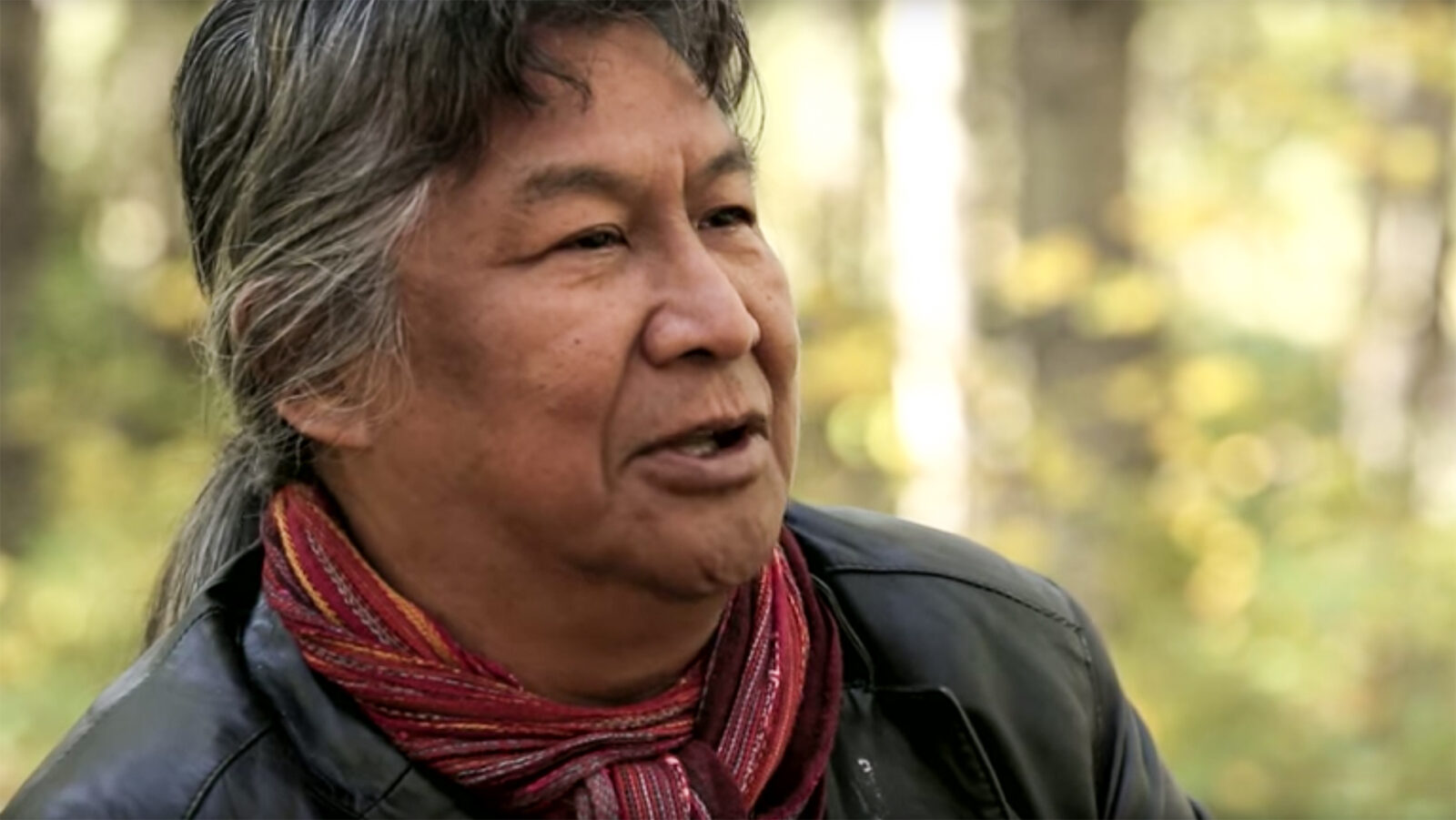

As Indigenous people, “we believe inherently that we are part of the Earth. We’re not separate. We don’t have dominion over it,” Stephen Kakfwi says. A former premier in Canada’s Northwest Territories, past president of the Dene Nation, and lifelong Indigenous rights activist, Kakfwi has spent decades working to balance protection of the mostly pristine areas of this landscape with sustainable economic development for First Nations communities.

The boreal region of Canada stretches across more than a billion acres, and is one of the largest intact forest ecosystems on Earth.

“What is closest to me is the land where I was born,” Kakfwi says. “Everywhere I look, there are stories. There are spiritual, sacred sites. And those are beautiful to me—in my heart and my mind, not just visually.”

Kakfwi was born in 1950 on the northern edge of the Territories’ vast boreal forest region near the Arctic Circle, at a hunting camp on the shores of Lake Yelta. He spent his early childhood in tiny Fort Good Hope, a Dene village along the 1,080-mile-long, north-flowing Mackenzie River, known in the Slavey language as the Deh Cho.

“There was literally nothing there. There was a little grocery store, a church, and that was it,” he says.

“For the first five years of my life, I lived off of moose and caribou, rabbits, ducks, and the berries that we find in the woods, in the bush. … We depended 100 percent on the bounties of the land, on the wildlife, the birds, the fish.”

Kakfwi’s connection to the land has shaped a career spent fighting for recognition of the rights of Indigenous people, including the right to make decisions about development and conservation on traditional territories where they have lived for thousands of years.

“The Dene have always had a plan for our land. Every year, for thousands of years, we have decided who’s going to go to the fish lakes, which families are going to go to the mountains, which ones are going to go on the river, which ones are going to go to the [river] delta areas. We decide that amongst ourselves,” he says.

“Where are the places where the moose are plentiful? Where is the best fish? Which areas should we leave [alone] for a few years until they become plentiful again? That’s land use planning, and that’s what we’ve done.”

“When you come into my country, I expect you to live as a good citizen, to respect the rights of everybody else, to take care of the land and the water and the wildlife, and leave it the way you find it,” he says.

“I’ve always carried that with me. And I think all our people carry that with us. And it’s no different from a person that lives in a city that has a yard. Nobody is going to go into that yard and contaminate it. I mean, it’s just totally unacceptable. So why should we be any different from that?”

“We have more and more people now that come to the North, make it their home, want to keep the land and water [healthy], but also have some responsible, sustainable development occur,” he says.

“We have slowly won the battle, where now we are—by law and by policy and practice—now in the room when mines are being planned, oil and gas projects are being developed. We have a say. We are consulted. Our consent has to be often sought. … Now, in the Northwest Territories, they talk to us.”

Kakfwi has never forgotten what he learned as a boy, when he sought out a small stand of birch for healing. The way to connect with the land, to learn to respect and use it sustainably, is to pay attention to the details, the small things and quiet places that make up the greater whole.

Whenever Kakfwi travels, he likes to take a walk to get oriented and to understand the new environment he is in. He studies the trees, the landscape, the birds overhead, and even the ants.

“Anywhere you go, if you haven’t been there before, you will feel a little bit lost, because you cannot see past the next tree. And so we encourage people to go for walks, to pay attention,” he says.

“And once you have that, your comfort zone is very, very different. You establish a relationship with yourself, with everything around you. And then you become a part of it.”